My Background

The first picture I took was of the view looking up into a wintertime tree in Sussex, England, where we lived. The structured complexity of its leafless branches fascinated me. I was eight. Genes often play a role in our destiny. My parents were “Creatives” both had won scholarships to study art.

Before he died, my father told me he spent the Second World War years entombed in the cramped most secret place in Britain, the Map Room, under Whitehall, the Government’s Command Centre. The endurance, secrecy, loyalty, dedication, and capability of these chosen few has only recently been recognised with the opening of the Cabinet War Rooms Museum. Sadly he never talked about his experiences, not even to my mother, and yet he would have been in the presence, at one time or another, of all the World Leaders.

Working as a commercial artist mainly from home – he had a darkroom in his studio. He showed me how to develop the film and print the picture of the tree’s branches. It was the start of what has become a lifelong vocation.

In those days, the education system regarded subjects like ‘Photography’ as suitable for a hobby but not serious study. However, our parents cared about my sisters’ and my education and chose well for us. At my senior school, Clayesmore in Dorset, England, I was actively encouraged and became instrumental in re-establishing the school darkroom. The space allocated could not have been better. It was in the basement near the heating boilers – a perfect solution to maintaining the magical 20°C for developing film. I spent many absorbing hours learning what would become the rudiments of my lifetime’s craft, including experiments in high speed photography. I had no flash and so used 3amp fuse wire between two mains terminals to get the effect. The light it created when blown by switching on the mains was sufficient to show and freeze-frame the crown when an object was dropped into a tray of milk.

Despite my as-then undiagnosed dyslexia, there were subjects on the formal curriculum that interested me but I wasn’t what you’d call academic. My core creativity was visual. I remember a few sunny afternoons staring out of the window of Mr Henbest’s geography class, wondering, amongst other things, if a giraffe would enjoy eating leaves off the row of lime trees opposite, and trying to visualise how high up its 18 feet stretched neck would reach.

In the end, I did finally pass my exams but then came the question of what to do with my life. My favourite curriculum subjects had been biology and chemistry. The school career advisor thought I might like to be a biochemist, so arranged a visit to a laboratory in Birmingham. It was an awful place: Dickensian, gloomy, with roof windows that had hadn’t been cleaned for years evidenced by the black underside of the moss growing on them. The Bunsen burners might have been used by Michael Faraday. The scientists I met there were fat bald men who had given up on the joy of life for a salary cheque. I was 17. It was 1966.

After the visit, I decided to have a few hours off before catching the train back to school. I went to a city centre cinema. Antonioni’s film “Blow Up” was playing. It changed my life. I had always greatly enjoyed photography but taking wedding pictures for a living was not my idea of a future. Antonioni showed me that photography could be a life’s path. The Rolls Royce convertible driven by David Hemmings, the actor playing the photographer and lead in the film, gave me the idea that a living could be made from this profession. Also, his life style was irresistibly sexy with a frisson of danger thrown in – all very appealing. So thank you, thank you, Maestro Antonioni.

With my career now firmly set in my own mind, I applied to the School of Photography, Regent Street, London, where the first degree course in photography had been established. I was interviewed by the legendary photographic historian Margaret Harker. My learning there has served me well. When the world changed in the late 1990’s from the chemistry of celluloid or analog photography to digital, it was so pleasing to find that the histograms and methodology of describing colour remained the same. All those hours plotting the graphs of processed colour film had not been in vain.

I was so lucky to be in the right place at the right time in a profession that was riding on the wave of the then new technology of inexpensive colour printing. Up until the 1970’s, newspapers were printed in black and white but the printing industry moved on as colour scanners and colour litho printing became viable. In particular, the Sunday papers began including a colour supplement. As ever, technology drove cultural change. With the colour print industry booming, every subject needed to be photographed in colour.

Only recently out of college, my first job was with the Telegraph Magazine, a story I presented to them being accepted, and I getting the prestigious front cover. Those were great days to be a photographer, not least because the technology was not that sophisticated and the colour supplements had to be printed weeks before publication. This meant that the subject matter had to be of ongoing interest rather than merely news-for-a-day. This fitted my preferred ways of working perfectly.

There has almost certainly never been a profession in history that has offered such geographic and social mobility as being a photographer in the late 20th century. The internet had not been invented and communication to all corners of the world was – at best – by telex, telephone and letter. Boards of directors considered the corporate annual report their connection to their shareholders, and I worked for some of the largest companies in the world photographing their acquisitions, assets and financially exciting innovations. I was particularly pleased when Tiny Rowland, its chief executive, told me that the LONRHO Annual Report had received a prestigious award, given that I had taken 80% of the pictures.

The work involved lots of travel, nearly always First Class as – possibly surprisingly – it was cheaper because of the weight of the equipment that, as a photographer, I had to lug around. One week I would be in Siberia taking pictures of a furniture factory, the next in Malaysia taking pictures of a rubber processing plant. As there was no internet (and indeed no digital reproduction), pictures of a very high standard were required for corporate annual reports and the easiest way to get them was to send me. The cost to the client could be eye-watering. Shell Transport and Trading once commissioned me to take a picture of a new drilling bit that could change direction when drilling. The offshore oil rig was in the Middle East. I landed on the platform, asked to see this new drill bit

and was told that it was 1400 feet below us. It had to be brought up for the photograph. When I was getting back into the helicopter three days later, the drilling captain asked if I knew how much that picture had cost? £350,000. I simply hadn’t thought about it. I was thankful that I had a portable refrigerator to keep the film cool while waiting for the plane back to the UK. When I got back to London I took the precaution to process one roll of film at a time to reduce the possibility of a processing error.

To stay for a moment on technical aspects to my work, the professional colour film we used back then had a latitude of half a stop. This meant that the exposure had to be exact – no Photoshop in those days. What was required was a perfect transparency ready to be scanned. It was a skilled business, and for those who developed a reputation for consistently producing outstanding images, there were huge rewards. The Arts as a profession, if you were good, was highly paid, it still is; though it has lost purchase as the internet undermines the need or respect for Copyright. I still enjoy the memory of reading an article in the Financial Times in 1989 on MP’s salaries, and realising that, in that year, I had earned more than Margaret Thatcher: the power of the market place. On the other hand, it did not matter whether I was working in a thunderstorm or tropical sunlight, in Jakarta or on a dull day in Glasgow, if I returned without a beautiful photograph that could be my last job and my reputation seriously tarnished: the rules of the ruthless Darwinianism of the market place.

In those days, before iPhone, a Sunday Times Press Card carried respect and photography was a privileged but also trusted profession. When I was photographing NASA astronauts in full kit practicing manoeuvres in a swimming pool that contained a Space Shuttle at The Johnson Space Centre in Houston, I was given 10 minutes of Shuttle re-entry in the simulator as a free bonus to my visit. There were no guards when I knocked on the door of 10 Downing Street in the early 1970’s to photograph Edward Heath, the then Prime Minister. But sometimes restrictions and security came in unexpected locations. To photograph the river Fleet that is now part of the sewage system under London, I had to wear high-security safety equipment and all my equipment had to be passed for use in an inflammable environment. In addition, there was a Police cordon around the road entrance to the sewer. You couldn’t help but feel privileged and not a little important in situations like that.

The feeling of being privileged, I often associated with my work, whether it be photographing washing machines manufactured in Italy or a crafts person making a stained glass window in Dorchester. I was taken into their working life and experienced how our economy harnesses this tapestry of human industry. I certainly felt privileged to be with an extraordinary group of American Adventurers who were looking to set up a joint US/Russian company. We were piloted by a high ranking Russian Air Force Officer in a yellow Illyushin helicopter to jump out on top of a mountain west of China and north of Afghanistan to ski down it for the first time in the earth’s history. The joy, excitement and the adrenalin makes me smile as I recall this assignment. Or listening to Pygmies drumming in the Congo rain forrest to thank the gods for our survival after a very intense electrical storm, was privileged indeed. Hunter Gatherers I was taught were an early and lowly human state. However these people’s everyday life was fulfilled and at one with their surroundings and I so enjoyed their laughter and songs that made up each day. I was also amazed that they could find wild garlic in the forest quicker than I could find a parking space at Tesco. All over the world we applaud the “Black Lives Matter” campaign. However, I heard stories of enslavement and murder of these gentle people, allegedly by local Bantu villagers. Their culture and harmony in their forest environment stretches back over 30,000 years. This achievement must hold lessons for today.

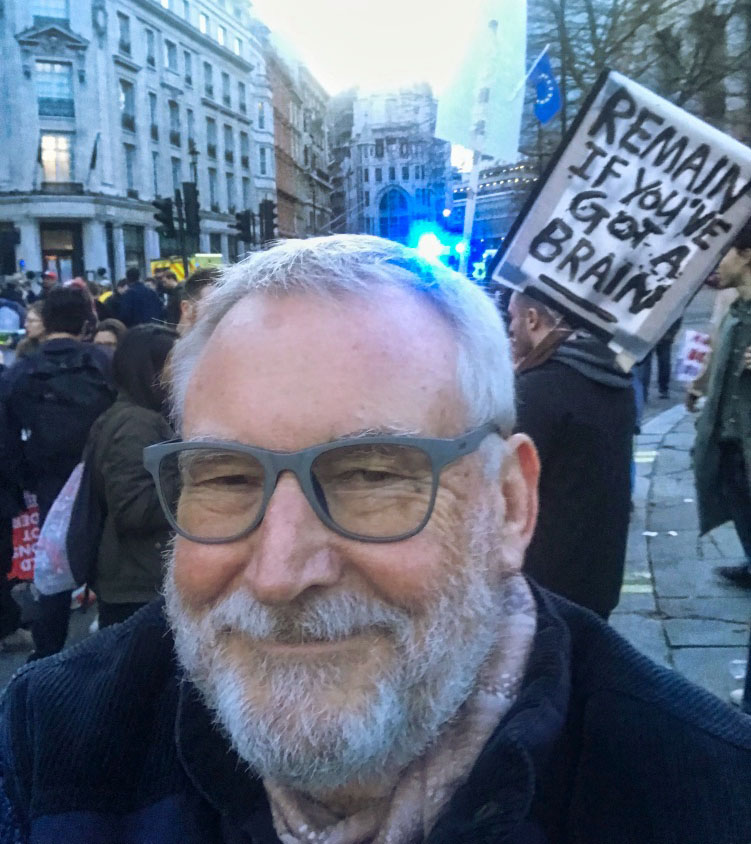

I have worked in 76 countries, in cities, deserts, farmlands, wildernesses, mountains, the Arctic Circle, on offshore oil rigs and the seas beneath them as well as in tropical rainforests. I’ve seen war and I’ve seen people caring for each other. I have developed a deep and concerned appreciation of the complexities of the ecosystems of this planet. Deep because they are amazing. Concerned because we humans are disrupting them so profoundly, by burning fossil fuels, that we are leaving future generations – including my own daughter – with grave challenges.

I have enjoyed my long career hugely and used my talent to the best of my ability. So, after all I’ve said, it may seem strange to tell you that my most treasured image-memory is of a picture that I chose not to take. I had hired a helicopter, had the doors removed, and was flying north out of Manila. This will have been in 1997. The sun was rising. Below was a steep valley striated with paddy fields. The red sunlight was reflected in the water of every field. It was stunningly beautiful and I remember that ‘photograph’ more than any other because I took it with my brain not with equipment. It is indelibly printed in my neurones.

And my most abiding non-photographic memory? All my meetings with kind people in all sorts of settings and walks of life. The world is not a scary place although, because of my work, I have been to scary places: been imprisoned for allegedly being a spy, targeted with guns, shot at, on one occasion had two spears put to my throat with serious intent. I have learned that almost always it is how you handle the moment that decides its outcome. Accidents and extreme ill-luck can happen, they are part of life, but to be purposely killed by another person that you can communicate with, is remarkably rare.

It was a cold rainy November day in London in 1979 when the Honourable Mark Tambatamba, then Minister of Information to the Zambian Government, contacted me to propose that I consider an assignment. You could say it changed my life. He and I worked together to produce the first pictorial book of his astonishing country, that was so well received that I was later offered Honorary Citizenship by President Kaunda. Over 30,000 copies of this book have since been published, actively contributing to giving Zambia an International platform. I feel privileged to have watched this wonderful country grow in so many different ways.

Ian Murphy

Lusaka 2020

With thanks to Miles Larmour who kindly helped with my dyslexic challenges.

A Brief Professional History

Work Experience:

2017-2018

Produced and published “Mural Paintings” and the first photographic Exhibition at the National Museum Lusaka

2013-2016

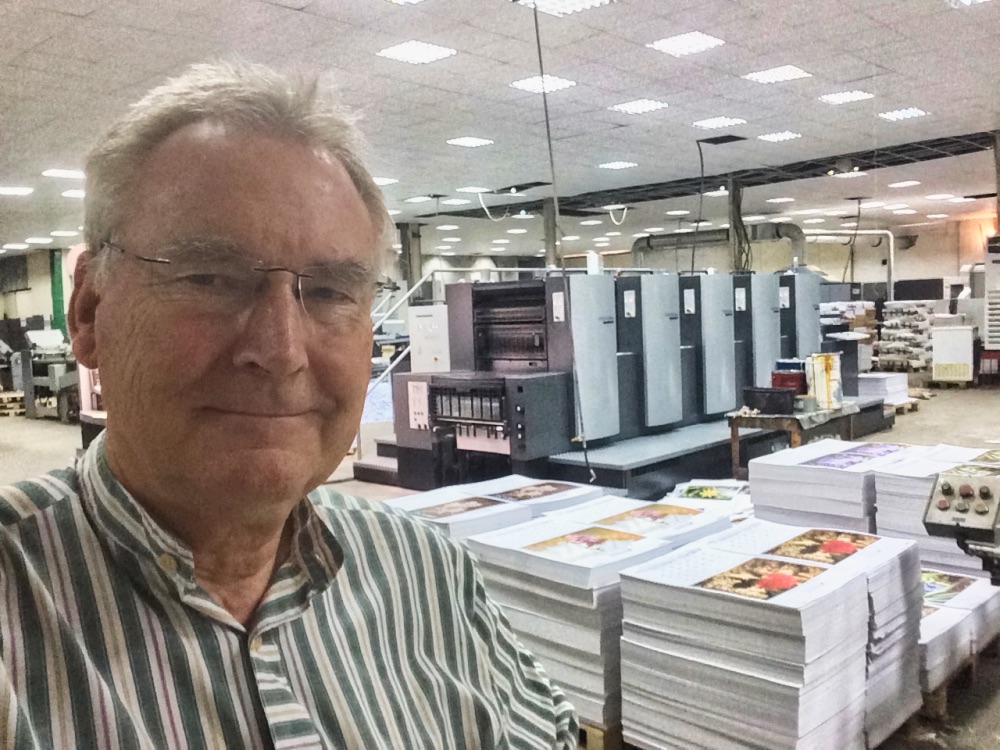

Produced and published “An Introduction to Astronomy” with a map of the sky printed with illuminous ink. “ZAMBIA Celebrating Zambia’s Golden Jubilee”

The print run of the LSA calendar reaches 4000.

2009-2012

Produced and published the first book on the Kafue National Park, a park of 22,400 square kilometers, and made a map of the park.

2000-2008

Produced and published “The Traditional African Art of Zimbabwe”

“The Historic Trees of Zimbabwe” “Food and Good Fellowship” “A Field Guide

to Planning and Implementing Land Use Changes with Rural Communities in

Africa” “Acacia Handbook” “The Magic of the Makishi” “Healthy Harvest” for

the FAO, “Showtime” for the Zambia Agricultural and Commercial Society, “African Organic Farmers Field Crop Manual”.

1994-1999

Produced and published “The Field Guide to the Acacias of Zimbabwe” “Kakuli” “The Spirit of the Zambezi” and “The African Catalina”. Won the European Union Funded Contract to produce 40 tons of brochures and posters for Zimbabwe’s Tourism Industry.

1989-1993

Produced and published “Zimbabwe – Africa’s Paradise” The Presidential Elephants of Zimbabwe” for the Heads of State Commonwealth Conference. Work experience in Russia, Kazakhstan, Georgia, Siberia, Singapore and Australia.

1986-1988

Developed a larger based corporate clientele, founded The Corporate Brochure Company in London to service the needs of this sector. Work experience in Thailand. Indonesia, Oman, Philippines, and Malaysia.

1983-1985

Photographic work for Corporate Clients – Annual Reports etc. Produced and published “Zambia”. Offered Honorary Citizenship of Zambia by President Kaunda.

1980-1982

Magazine assignments including work in Spain, Italy, France, Sweden, Denmark, Mexico, and the USA.

1977-1979

Developed knowledge of the printing industry with the completion of “Rhodesian Legacy” published by Struiks, Cape Town, after a commission from the Rhodesian Tourist Board. Work experience in the Advertising Industry. Freelance assignments in the UK for The Telegraph Magazine, The Observer Magazine, The Sunday Times Magazine and others.

1972-1976

Photo-reportage. Main client: The Telegraph Magazine.

Clients:

Shell UK, Shell Transport and Trading, Burma Oil, Petroleum Development Oman, Glaxo, Britoil, Rolls Royce, Lonrho, Alfred McAlpine, The European Union, The British Council, Zambia National Tourist Board, Zimbabwe Tourism Authority and others.

Awards:

“The Most Original or Imaginative Treatment of Building Services” by HVCACIBS Journal.

“Wildlife Photographer of the Year” 1986.

Winner Castrol Industrial Photographic Competition “Picturing Industry” 1987.

Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society London FRGS 1998